You’ll remember last week I discussed my philosophy on fuel dumping and whether or how much of the technique should be shared openly. This week I’m going to tell you a little bit about how to do it yourself. A lot of it can already be found in my posts on MilePoint. However, some could use more clarification.

Reminder: if you have complaints about how much I’m sharing, please send me an email explaining which part should be edited and what a satisfactory solution would look like. I think very carefully about what I include. A lot of this has been shared publicly elsewhere, so while I may agree to remove SOMETHING, I will not remove EVERYTHING. If you want me to make changes, you must tell me what changes are necessary.

- Part 1: Introduction to fuel dumping

- Part 2: Finding and booking a 3X

- Part 3: Variations and advanced strategy

Basics

With the rise in oil prices in recent years, many airlines have taken to adding fuel surcharges to their international fares. Some of them even make you pay the fuel surcharge when you book an award trip, claiming that the miles only cover the base fare (which is total BS, but that’s another story).

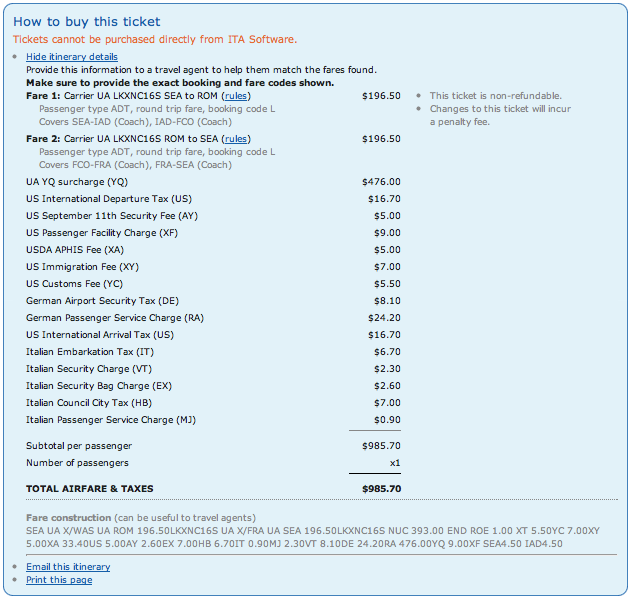

The result is that many (but not all) international fares include three components: (1) base fare, depending on the fare or booking class like L or Y for coach and Z or C for business; (2) taxes and fees imposed by governments and airports; and (3) fuel surcharges. Some airlines still include fuel surcharges in the base fare, and others may break them out only for certain routes. However, when a fuel surcharge exists, there is often the potential to dump it.

Why include fuel surcharges in the first place? I’m not entirely sure. I don’t believe it was done just to make people pay fuel surcharges on award tickets. That’s a bad customer service decision when the fees and fuel surcharge may cost more than a discount revenue ticket, and clearly some airlines (mostly U.S. airlines) manage to survive without doing it. I think a better explanation is that airlines can easily adjust the cost of a ticket by changing just the fuel surcharge that applies to many routes between two regions without adjusting the base fare for each individual route as well as the dozen or so fare classes on each flight.

When you get into this hobby, you may notice that the fuel surcharge between the U.S. and Europe is one price on PanAm, but a different price on TWA. It’s yet another price on PanAm if you are instead flying from the U.S. to Asia. It makes sense from the perspective of individual carriers trying to easily adjust fares in response to their own fuel expenses to each region even if we as consumers don’t always like the way it’s been implemented. For example, fuel surcharges haven’t really fallen much even as the price of oil has dropped significantly.

Since this is called fuel dumping, that means you can’t dump a fare without a fuel surcharge. Taxes and fees are generally fixed, so I don’t worry about them. A few special cases include the example of flights out of London, where the UK has imposed a large air passenger duty (APD) on departing flights. A way to avoid this is to originate your trip in another country but pass through London as a connection. But again, this is an example of a special case and not something I worry about.

Candidate Fares

What you should worry about is finding flights with low base fare and high fuel surcharge, generally designated as YQ (sometimes YR) in the fare construction that you can find through ITA or other fare search engines. Base fares between the U.S. and Europe may be $80 each way in winter and $120 in summer. The reason the price you see is so high is that the fuel surcharge can be $500 plus an extra $100 in taxes. Dump the fuel and fares as low as $200 between New York and Europe are not unheard of. These low base fares are called “candidate fares” and are not all that difficult to find. Just look for low total fares and check the fare construction to see how much of it is YQ. If it’s just low because the base fare is $200 each way and there’s no fuel surcharge, then this fuel dumping technique isn’t going to help you at all.

Per the comments below, I’d like to clarify that a low base fare is not critical. However, it is important that there be sufficiently large YQ (or a very effective 3X) that a fuel dump be able to lower the fare by a worthwhile amount. If the YQ is $100, it probably isn’t worth the effort.

For example, here is a fare to Rome that I’ve been researching lately. Not a terribly good candidate, but you can see that even so, YQ of $476 makes up about half the total ticket price of $985.70. For a good candidate, the YQ can be over three-quarters of the all-in price since the YQ doesn’t vary due to seasonal demand or occasional sales.

Candidate fares are easy enough to find that they often aren’t coded at all; people just post the entire fare construction with dates and airlines and flight numbers. I’m ambivalent toward this approach. On the one hand, certain valuable itineraries that can be brought to very low prices should be coded because if too many people find a working dump and succeed in booking it, the fare could disappear and the dump stop working. It may not be a Tiffany jewel just yet, but we can all agree that it’s not wise to leave rough diamonds lying around unguarded. On the other hand, no one wants to decode the question just so they can create and code an answer to it. Less would be accomplished if everything were coded.

Third Strike

The critical tool to make fuel dumping work is the “3X” or “third strike.” A normal fare might look like A-B-A. Two legs from A to B and back. A dumped fare might look like A-B-A,X-Y. The same A-B-A trip with an additional X-Y leg tacked on as part of a multi-city itinerary. However, you don’t fly X-Y. If anyone asks, you fell ill while changing a tire on the side of a road in the middle of a snowstorm because you were in a funeral procession for your recently deceased great aunt Hilda. Something came up. Because typically X-Y is in some remote part of the world that you can’t easily get to.

Of course, sometimes X-Y is nearby, and X or Y may even be the same as A or B. But it doesn’t have to be, and I think that’s where a lot of people get tripped up. Just because I am trying to dump a fare from Seattle to London does not mean that my 3X needs to originate in Seattle. The route construction for a dumped itinerary is A-B-A,X-Y and not A-B-A-Y. That comma is key. Just like in Eats, Shoots & Leaves.

[Yes, I am a huge fan of the Oxford comma. I'm a man who knows his cocktails, fare construction, and grammar. That and I get to use a microscope that can visualize individual blood cells coursing through a fish. Is it any wonder I get all the chicks? ![]() ]

]

Words of Caution

Of course, the airlines don’t particularly like you doing this, so if you want to get any frequent flyer miles for this it might be wise to schedule X-Y for a month after you return to A, making sure that you have enough time for the miles to post before you “miss” your 3X due to some “totally unforeseen” event. This is also why the 3X happens last. If you put it at the beginning of your itinerary and miss it, the rest of your ticket will be cancelled, too.

Finally, don’t tell anyone working for an airline or travel agency or in any remote position of authority about what you are doing. If anyone does some digging and sees that the fuel surcharge is missing and what you’ve done to achieve that, they could easily cancel your ticket and close that 3X off to everyone else in this game. So don’t whine about seat assignments. Don’t try to reschedule your flight or do a same-day change. Don’t ask about upgrades. Just accept that you are getting a steal on this flight and the miseries of being treated like a non-elite passenger in coach are part of the bargain.

I will talk about how to find a 3X and other variations on fuel dumping strategy later this week, so make sure you are proficient at using ITA before then. Check out my three-part series on using ITA if you haven’t already:

The post Introduction to Fuel Dumping appeared first on Hack My Trip.